What Went Wrong? : Deciphering Sino-India 1962 War

The 1962 Sino-India War, which lasted from October 20 to November 21, 1962, was India’s first encounter with jarring geopolitical realities amidst its political naivety. India suffered a crushing defeat, with around 1,383 Indian soldiers made supreme sacrifice. About 3,968 Indian soldiers were taken as prisoners of war (POWs). India lost around 38,000 square kilometres of land in the Aksai Chin region, which remains under Chinese control to this day. On the other hand, China reported about 722 soldiers killed. With such a disparity in the aftermath casualties, it becomes imperative upon us to assess what went wrong. In this piece, we’ll try to make sense of this humbling defeat and the major takeaways for India. Furthermore, this piece will also throw light on the global landscape at that time as well as how other nations were looking at it, mainly the US, Soviet Union, and Pakistan.

SINO-INDIA 1962 WAR: INDIAN SHORTCOMING

POLITICAL MYOPIA AND POLICY FAILURE

Misjudgement and criminal negligence on the part of Indian political leadership was the numero uno factor behind India’s defeat against China. The Nehru government was living in a fool’s paradise vis-à-vis Indian territorial sovereignty. PM Nehru even intended to scrap the Indian army post-independence. Major General DK “Monty” Palit in his book on the biography of Major General AA “Jick” Rudra mentioned this anecdote. Shortly after independence, General Sir Robert Lockhart, as the army chief, took the defence policy plan to PM Nehru, and Nehru’s reply flabbergasted everyone. PM Nehru took one look at the paper lost his temper and shouted, ‘Rubbish! Total rubbish!’, ‘We don’t need a defence plan. Our policy is ahimsa (non-violence). We foresee no military threats. Scrap the army! The police are good enough to meet our security needs’. Nine days later, Pakistan attacked Kashmir in 1947.

MILITARY DISPARITY AND COMMAND FAILURE

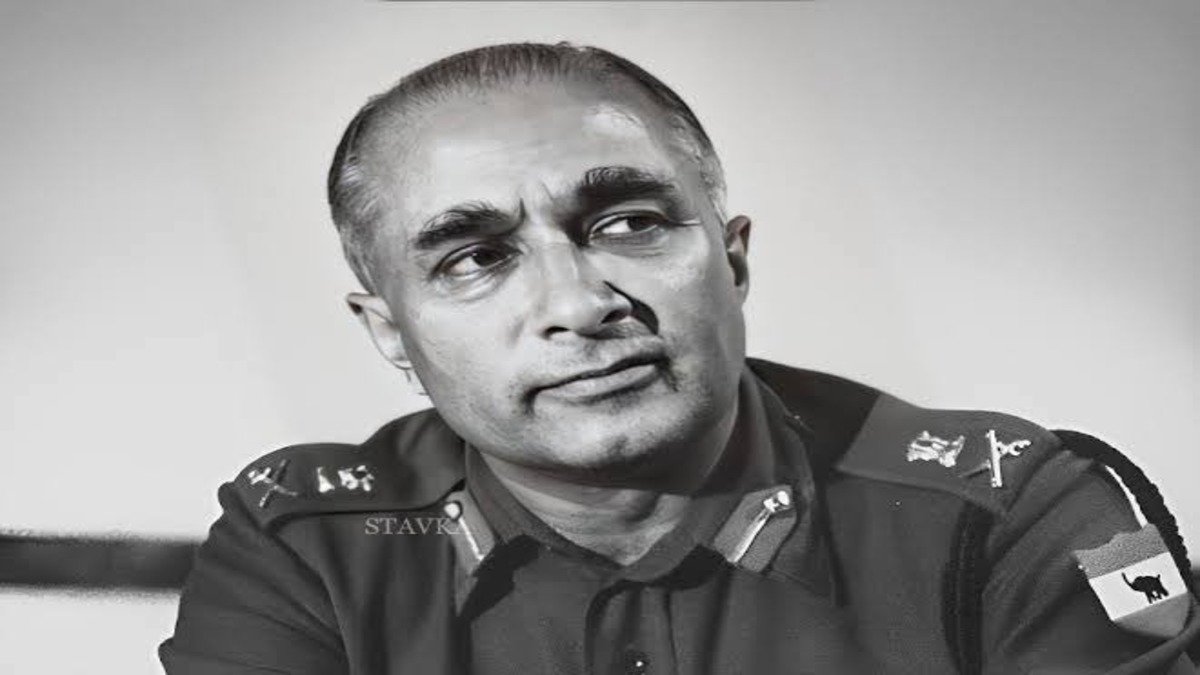

The Indian military leadership was indecisive and poorly coordinated. India’s military command structure suffered from a lack of coordination. Furthermore, there was poor coordination between civilian leaders and the military. These faultlines were on display in the Tawang Sector, where the commander of the IV Corps, Lt Gen B.M. Kaul, tasked with “ousting PLA,” fell short and was incompetent. General B.M. Kaul, who was given command of the Eastern Sector, lacked experience in combat operations and mountain warfare. Moreover, IV Corps was headquartered at Tezpur, without adequate ground intelligence, without sound logistical support, and handing over such a crucial front to an officer of questionable competence, Lt Gen B.M. Kaul, directly reflected command failure on the part of Nehru and Menon.

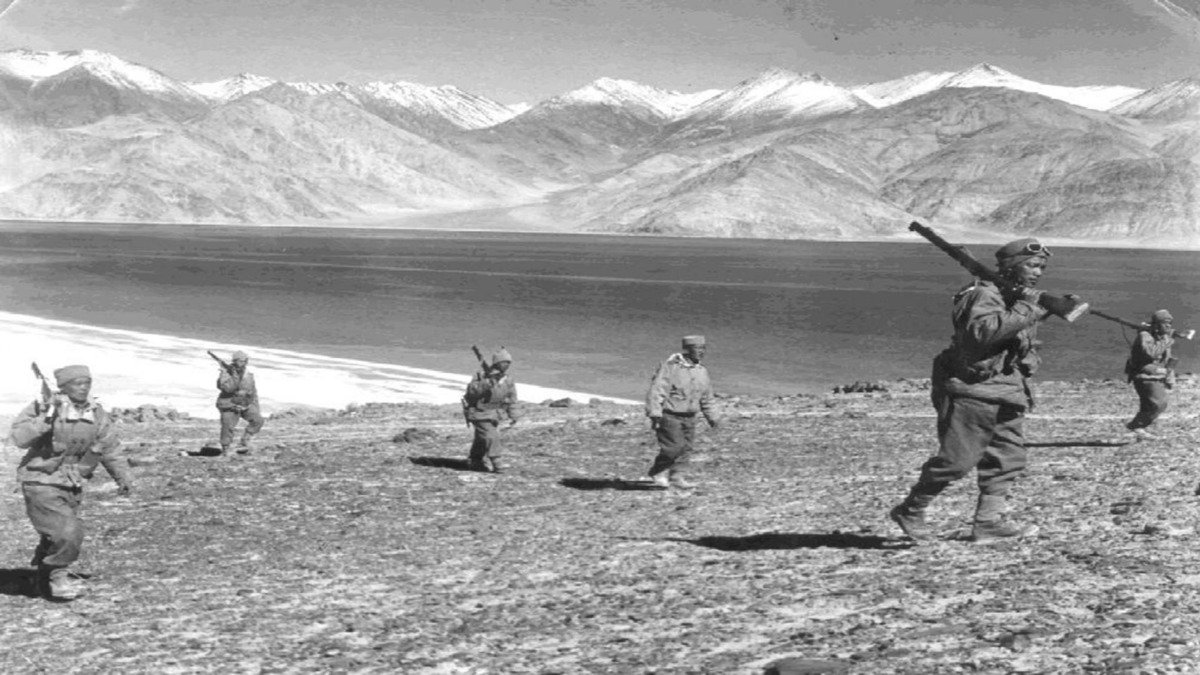

Apart from a lack of cohesion and coordination, another shortcoming was the evident disparity between China and India in terms of military preparedness and power. China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was much better trained and equipped in high-altitude warfare. They used superior tactics, such as infiltration and surprise attacks, to outmanoeuvre the Indian forces. India’s army, by contrast, lacked adequate winter clothing, weapons, and ammunition for a prolonged campaign in the harsh Himalayan terrain. Indian troops were poorly equipped for high-altitude warfare, and logistical support was limited. In contrast, the Chinese had better supply lines and infrastructure and had superior weaponry, including artillery and heavy equipment suited for mountain warfare.

INADEQUATE INFRASTRUCTURE AND LOGISTICAL SUPPLY LINES

India’s lack of infrastructure during the 1962 war with China was another major factor in its defeat. Poor roads, inadequate logistics, and underdeveloped border defence systems severely hindered India’s ability to deploy and sustain its forces. Indian forces struggled in frontline deployment due to the lack of all-weather roads. Troops had to traverse difficult mountain terrain, often on foot, which delayed their arrival at key locations. The lack of proper roads made it difficult to transport artillery, tanks, and other heavy weaponry to the forward bases, leaving Indian soldiers at a significant disadvantage in terms of firepower. The northeastern and Himalayan border regions where the fighting took place, such as Ladakh and Arunachal Pradesh, were extremely remote with no proper road network. Surprisingly, it was a conscious understanding within Indian political leadership to keep borders underdeveloped so that it would be difficult for China to walk into India.

On the contrary, China had already built a network of roads and highways in Tibet and Xinjiang, especially the strategic Aksai Chin Road (connecting Xinjiang to Tibet through Aksai Chin), which enabled the rapid movement of troops and supplies. Their forces were well-positioned and could move with ease, giving them a significant logistical advantage over India. Unlike China, which had better developed its side of the border infrastructure, India lacked airbases close to the conflict zones. China, on the other hand, used its superior roads and airstrips to maintain better logistical and military support. India had not established adequate military outposts or defensive fortifications along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). This left vast stretches of the border undefended, allowing Chinese forces to advance quickly and overwhelm the poorly positioned Indian troops.

AFTERMATH: REVAMPING DEFENCE STRATEGY

India’s defeat in the Sino-India War rang alarms in South Block. The writing on the wall was clear: an overhaul of defence policy is what was the need of the hour. The conflict exposed critical weaknesses in India’s defence preparedness, leading to a reassessment of military policies, reorganisation of defence institutions, and modernisation of the armed forces. Here are some of the key changes that were implemented immediately after the war:

EXPANSION AND MODERNIZATION OF ARMED FORCES

The biggest shortcomings encountered by Indian forces were a lack of manpower and modern weaponry. To address this issue, India, by 1963, tripled the defence budget compared to pre-war levels. India began acquiring advanced weapon systems from various countries. India acquired new fighter aircraft, such as the MiG-21, from the Soviet Union and expanded its air defence capabilities. It further sought to modernise its artillery and tank regiments, both of which had been deficient in the 1962 conflict. India also undertook a massive expansion of its armed forces. The Indian Army expanded its size significantly to enhance our defensive capabilities along the Chinese and Pakistani borders. The year 1965 saw the creation of the BSF to guard India’s borders and prevent incidents like the Chinese incursion in 1962. The BSF became the primary force tasked with ensuring border security in peacetime and assisting the army during wartime.

HIGH-ALTITUDE MOUNTAIN WARFARE

Post-1962 defeat, there was a lucid realisation within defence quarters regarding the gravity of having specialised troops for high-altitude and mountain warfare. The Indian armed forces created special training schools to train soldiers for combat in challenging mountainous terrain. Several new mountain divisions were raised for specialized high-altitude warfare training to better defend the Himalayan frontiers. The Army’s High-Altitude Warfare School (HAWS) in Gulmarg, Jammu and Kashmir, became one of the world’s leading training centres for mountain warfare. To train its forces in high-altitude warfare, India began raising the “mountain strike corps” to enhance its offensive and defensive capabilities in the mountains. As a result, today India has the world’s largest and most lethal mountain fighting force in the world, a fact even the Chinese defence expert had to acknowledge. India’s victory in Siachen is yet another unrefutable example of the proficiency of India’s mountain warfare.

BORDER INFRASTRUCTURE DEVELOPMENT

It’s an age-old adage: An army is as good as its logistics, and that’s where India lost to China in the 1962 war. India lacked border infrastructure, especially roads and airstrips in the mountainous regions. Consequently, India began a focused effort to build better infrastructure in the border areas. India initiated programs to develop 70 strategic roads, with a length of 4,000 kilometres, for construction along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Key road projects include the Darbuk-Shyok-Daulat Beg Oldie (DS-DBO) Road in Ladakh, which connects Leh to Daulat Beg Oldie near the LAC. India further extended the rail network in the border areas, which includes the Tezpur-Tawang railway line, the Bilaspur-Manali-Leh railway line, etc. For all-weather connectivity, India developed bridges and tunnels, including the Atal Tunnel, Sela Tunnel, etc. India has further revived and upgraded several advanced landing grounds in Arunachal Pradesh, including Vijaynagar, Mechuka, Pasighat, Tuting, Walong, etc.

BOLSTERING INTELLIGENCE NETWORKS MECHANISM

The failure to preempt and prevent Chinese aggression was seen as a significant intelligence failure. As a result, efforts were made to strengthen India’s intelligence-gathering and assessment capabilities. Post-1962 Sino-India War, Indian defence establishments set up intelligence networks monitoring Chinese activities across LAC. It was the crushing defeat in the 1962 war that led to a complete overhaul of the Indian intelligence paradigm. This later culminated in the formation of the Research & Analysis Wing (RAW) in 1968 by R.N. Kao. R&AW became India’s external intelligence agency with R.N. Kao as its 1st Chief. Furthermore, steps were taken to improve coordination between India’s intelligence agencies and the military leadership to prevent future intelligence lapses.

Also Read, What If India and China Were Allies?

GLOBAL RESPONSE TO THE 1962 SINO-INDIA WAR

U.S. RESPONSE

The United States saw the war as a direct result of China’s aggressive expansionist policy. The U.S. viewed China’s attack on India through the lens of the broader global struggle between communism and the free world. Despite India’s non-aligned stance, the U.S. saw an opportunity to counter China’s influence by providing military and diplomatic support to India. The U.S. responded quickly by providing India with military equipment, including arms and ammunition, as well as offering airlift assistance to transport supplies to the Himalayan region. The U.S. also considered direct military intervention, but this was ultimately avoided due to the brevity of the war and India’s reluctance to escalate the conflict. President John F. Kennedy’s administration firmly backed India during the war. Kennedy expressed his solidarity with India, and the U.S. condemned China’s actions as blatant acts of aggression. The war opened the door to closer U.S.-India relations.

SOVIET UNION RESPONSE

The Soviet Union’s response to the Sino-Indian War was complicated by its strained relationship with both India and China. The Soviet Union initially maintained a policy of neutrality and called for a peaceful resolution to the conflict. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, despite being at odds with China, avoided outright condemnation of Beijing’s actions, likely out of concern that further escalating tensions with China could weaken the Soviet bloc. As the conflict progressed and it became clear that China would not heed Soviet advice, the USSR began tilting more toward India. By the end of the war, Soviet support for India became more visible, particularly in terms of military supplies and diplomatic backing. The Soviet Union’s ties with India deepened in the years that followed, with India relying heavily on Soviet arms and technology.

PAKISTAN RESPONSE

Pakistan monitored the Sino-Indian War closely and shaped its response based on its ongoing conflict with India over Kashmir and its growing alignment with China. Pakistani leaders welcomed China’s move against India, hoping it would distract and diminish India’s military capacity, thereby giving Pakistan a strategic advantage in the region. During the war, Pakistan maintained a neutral stance publicly but went westward to China in its backstage manoeuvres. The war was a catalyst for a deeper relationship between Pakistan and China. Soon after the war, Pakistan and China began formalising their strategic ties, including signing border agreements and increasing military cooperation. Some Pakistani analysts viewed the war as a missed opportunity to launch its military operation against India, particularly in Kashmir. However, Pakistan refrained from opening a second front, possibly due to concerns about international backlash or the uncertain outcome of a two-front war against India.

CONCLUSION

The 1962 Sino-India War was a pivotal moment in India’s military history, exposing critical flaws in its defence strategy and preparedness. It is fair to say that it was a traumatic but transformative event for India. The lessons learnt from that defeat drove India to modernise its military, improve its infrastructure, and adopt a more robust defence strategy that continues to evolve in the face of changing regional dynamics. The war came as a wake-up call for India to course-correct its defence policy and position itself as a significant military power in the region. Today, India’s military is vastly more capable and prepared, in part due to the painful lessons learnt in 1962. The fact that India has never lost a war after the 1962 conflict—including the 1967 Nathu-la war with the same China—allows one to evaluate this.